I spent six months at a PE arm of a government-affiliated fund. The primary motivation was joining for private equity industry rather than joining a government-related organization. However, some traits may be shared across those types of organizations — here are three challenges I have observed.

1, Lack of ownership: who is your customer?

This may be the most critical matter. The compensation of the people working in the organization is all indirectly paid by taxes. In the private sector, the wages come from the money that businesses make. The cash flow complexity differs by type of business — if you work at a noodle restaurant, your compensation would be based on the number of noodle bowls people consume. In typical private equity, your “customer” will be LP (primarily institutional investors) who invest in your fund.

The restaurant industry is one of the most accessible industries to understand what your wage is based on, and hence it is easier to know what you need to get your paycheck. Serve tasty food, friendly service, and provide a good experience for customers coming into the store. You can even do a quick calc —Let’s say you earn $3,000 a month, and your business generates 10% profit out of a $7 noodle bowl. You need to sell 4,286 bowls (3,000/0.7) to get your monthly paycheck (note: in reality, your salary comes from labor cost, and profit is after that labor cost, but this is a simplified example).

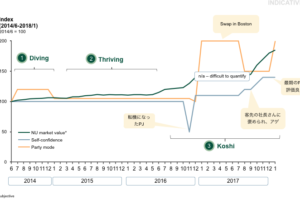

At a “private” private equity (sounds odd but to be accurate in this case..), you need to pay back to your LPs with returns. Some of them may be very tough and harsh, particularly when funds are not generating enough returns. It’s not those LPs that bring you profit, but you can imagine where the money comes from (≒customer). Therefore, particularly senior people who raise money have strong ownership.

If you can imagine who your customers are and understand the flow of money, I believe people can feel more ownership to their work — i.e., understanding why you do what you are doing now.

Who pays the taxes? Us. It’s straightforward. It is difficult to imagine the face of the people who pay the cash (tax) as — yourself, friends, families, and all other people in the country are included. In a way, you could imagine the group of people, but it is not specific, so it makes it vague to track the source of your paycheck.

My organization had a lot of dry powder (i.e., money that is not yet invested), which typically causes LPs irritation. They don’t prefer their money to be reserved as cash (as it won’t generate any returns). In my case, since the funds were ultimately coming from tax, technically, LPs were Japanese nations. People I worked with were extra careful about the money due to its uniqueness (coming from tax). There were a lot of discussions that we should be extra cautious about choosing where to invest in and how that would impact the (Japanese) industries or society. But again, if we reserve the cash in the form of cash, that won’t generate any returns. So we should feel the pressure, and I do think people did — but maybe not enough. Compared to a “private” private equity, the pressure was seemingly low, and the lack of ownership stemming from the vagueness of LP (payer of the money we manage) was one of the big reasons.

2, Capability gap: A civil servant transforms into a “fund manager”?

One of the odd things I felt while working there was to see the people transferred from various government ministries. At least here in Japan, it is common practice that the civil servants working in government ministries take different roles every 2–3 years. For instance, a person working on IT strategies of Japan may then work on nuclear issues in the next three years, then move to the ministry of agriculture for two years.

This is, to an extent, a common practice among traditional Japanese companies too. The idea is to raise balanced “generalists” through various experiences than to raise “specialists.” It might have made sense decades ago when 90%+ people worked in the same organization for 40 years. It is, in my opinion, getting less and less relevant for this fast-paced world. I find it interesting to speak with people who know various things than just knowing one thing; however, professionally, I would like to work with people with specialties.

So what happens then? Multiple people transferred from various ministries (e.g., MoF, METI, MHLW, IPO*) to the fund. They come in with “Director of Corporate Strategy” or “Partner at Venture Capital,” etc. When they first go in there, most people start their jobs by saying, “I have never been exposed to any works related to ‘investment’ or any businesses, but I will do my best.” And they will typically leave in 2–3 years (max five years) until government ministries HR give you another (somewhat random) mission.

To be fair — most of them are “good people” with a strong public mind to do something good for the country and have worked (hard) on various projects. They just don’t have the investment or business experience. Ironically, they don’t even get paid more by earning those titles (as their compensation will remain as government standard, which is typically lower than the corporate world.) An associate coming from IBD may be earning more than a “Director” coming from the government. It is an issue on the government side system instead of each person’s capability matter, causing strange internal structure that may negatively impact the governance.

I agree more knowledge/people transfer between public organizations and business organizations to understand its meaning in the long run. But I am also a little puzzled how we utilize billions of dollars of dry powder, competing with professional investors domestically or globally.

*MoF = Ministry of Finance; METI = Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry; MHLW = Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; IPO = Intellectual Property Office

3, “Dual-role”: capacity and mindshare issue

Not sure if this is the correct phrase, but “dual-role,” i.e., one individual taking multiple roles, is somewhat familiar in Japanese organizations (not just at government-related but also at many private companies; “兼務” in Japanese). For instance, one individual may be a director of divisions A and B even when the nature of businesses are very different from each other. Or, one may be a director of division A and the head of section x underneath division A. Typically, when these people get this kind of additional assignment (director of division B or head of section x), they typically won’t get additional compensation. Instead — it is often regarded as “rewards”. Social status is maybe more important in Japanese society than that is in other countries, and hence even if it does not come with additional compensation (more works though), many people (particularly 40yrs+ old gentlemen) sort of taking it as a prize, feeling “I am such an important person for the company.”

It’s excellent (from a company perspective) if those individuals regard those additional roles as prizes and get motivated without paying more. There are two issues here.

(i) The first one is the physical capacity issue. In reality, unless that person had a lot of blank space on its workload, they cannot fulfill the role, as you can imagine. They may get motivated, but since it is also true that they don’t get additional rewards, so the ownership of working hard for division B or section x becomes weak.

(ii) The second one — and I think this may be more tricky — is mindshare. Let’s say you spend time on division A and B 50:50, and A is generating profit while B is struggling. You need to work hard on Section B to make it better; however, you may rely psychologically on A as it generates profit as-is and thinks you are not too bad. It’s sort of “escape” — yes, it’s hard to be facing with section B 100%, and physically, there may not be so many works to do (let’s say 80%). However, if you have that 20% blank space when B is struggling, you will naturally think, “what else can I do to make B better” which may not occur if you do A and B 50:50.

Back to the fund I worked for — the fund was formed about a year ago and had dry powder (as noted). It was a succession of another fund over 6–7yrs with multiple portfolio companies. Most middle-senior people came from that organization and worked on both the previous fund and the new one (“dual-role.”). I joined 100% for the newer ones, and so as the other junior people. When there are few portfolio companies, the priority is to INVEST, as otherwise, you cannot generate any returns. Making a new investment is not an easy job and requires lots of analytical and networking skills, in which senior people tend to have strength. Most middle-senior people had “dual-role” and did not seem to have allocated enough time on sourcing which takes time and effort. Since there were no portfolio companies, I was probably under more substantial pressure as otherwise, I did not have many things to do.

I understand government-related organizations tend to have different dynamics, priorities, and agendas from the corporate world. I think there is a value that these types of unique organizations can add to the investment world, but the hurdles are not so low.

Please note that a lot (or all) findings might be particular to the organization in Japan.

コメントを残す